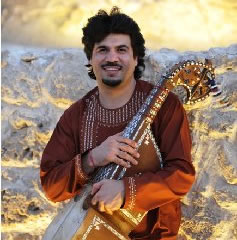

Homayoun Sakhi is the most outstanding and innovative Afghan rubâb player of his generation, a brilliant virtuoso endowed with a charismatic musical presence and personality. The rubâb is the national instrument of Afghanistan. Homayon’s artistry demonstrates how an imaginative musician working within a traditional musical idiom can enrich and expand its expressive power while respecting the taste and sensibility passed down from master musicians of the past. Moreover, Sakhi is the Founder and Co-founder of today’s two foremost Afghan music ensembles, THE SAKHI ENSEMBLE and Sounds and Rhythms of Afghanistan (SARA). His soaring technique, melodic flair and unparalleled style have earned him global acclaim as the maestro on Afghan rubâb.

Sakhi was born in Kabul in 1976 into one of Afghanistan’s leading musical families. From the age of ten, he studied rubâb with his father, Ghulam Sakhi, in the traditional form of apprenticeship known as ustâd-shâgird (Persian: “master-apprentice”). Ghulam Sakhi was a disciple and, later, brother-in-law, of Ustâd Mohammad Omar (d. 1980), the much-revered heir to a musical lineage that began in the 1860s, when the ruler of Kabul, Amir Sher Ali Khan, brought classically trained musicians from India to perform at his court. The Amir gave these musicians residences in a section of the old city adjacent to the royal palace so that they could be summoned to court when needed, and this area, Kucheh Kharabat, became the musicians’ quarter of Kabul. Over the next hundred years, Indian musicians thrived there, and Kabul became a provincial center for the performance of North Indian classical music.

The royal patrons of this Afghan-Indian music also loved Persian culture and classical Persian poetry. To please their patrons, the Kharabat musicians created a distinctive form of vocal art that combined elements of Persian and Indian music. One of the principal Persian verse forms is the ghazal. Ghazals provided the texts for the new style of Afghan vocal music based on the melodic modes (raga) and metrical cycles (tala) of Indian music. The Kabuli style of ghazal singing later spread to other Afghan cities. The tabla, the pair of drums used in this new music to accompany the rubâb and express the music’s sophisticated rhythmic element, is indisputably Indian, but its creators seem to have drawn inspiration from older forms of Central and West Asian kettle and goblet drums.

The rubâb itself is a classical instrument with a folkloric past. It originated in Central Asia as long as 2000 years ago, and belongs to a family of double-chambered lutes that includes, among others, the Iranian târ, Tibetan danyen, and Pamir rubâb. After the rise of Islam, the rubâb was used to play a devotional style of traditional Afghan music called Khaniqa. The instrument then had five gut strings for melody and no sympathetic strings. Today, it has just three melody strings, made of nylon, and 14 or 15 sympathetic steel strings. The rubâb’s heavy body is constructed in three wooden parts: a carved hull, faceboard and headstalk. Goat skin is stretched over the body’s open face, taut like a banjo, and the melody strings pass through a bridge made from a ram’s horn. The classical rubâb technique developed under the influence of Indian and Persian music is almost like claw-hammer banjo picking, resulting in parallel melodies, incorporating both low and high drones interspersed with melody.

Homayoun Sakhi’s personal story illustrates the extraordinarily challenging conditions under which he and his fellow Afghan musicians have pursued their art. During Afghanistan’s long years of armed conflict, when music was controlled, censored, and finally, banned altogether, the classical rubâb style to which Sakhi had devoted his career not only survived but reached new creative heights. Sakhi’s musical studies were interrupted in 1992 when his entire family moved to the Pakistani city of Peshawar, a place of refuge for many Afghans from the political chaos and violence that enveloped their country in the years following the Soviet invasion of 1979. In Peshawar, Sakhi became a popular entertainer, playng a mixture of ragas and popular songs. Sakhi recalled, “I earned a good income from music. I played on television and on the radio. Peshawar has a lot of popular singers, and I played with many of them.”

The unofficial headquarters of Afghanistan’s émigré music community in Peshawar was Khalil House, a modern apartment building where some thirty or forty ensembles, including many Afgahn exiles, established offices. The building became the headquarters for musicians available to play wedding parties and other musical events. Some musicians ran their own music schools, and informal jam sessions where young musicians competed to show off their virtuosity and technical skills were common. Long hours and a spirit of camaraderie in Khalil House enabled the musicians from Kabul to maintain and further develop key musical skills.

Sakhi rented a room in Khalil House and opened a small music school. “The people of Peshawar,” Sakhi explained, “the way they play the rubâb is different. I introduced a Kabul style to them. For example, traditionally, rubâb players didn’t touch the instrument’s sympathetic strings, but I use them a lot, in addition to the melody strings. Before, players just picked down with the plectrum, but I picked both up and down. I thought these things up. I listened to violin music from different places, and to guitar and sitar music, and symphonic music. I listened to a lot of different things that I found on cassettes, and I wondered, why couldn’t I play with these kinds of techniques on the rubâb? I started to try them. I understood that the rubâb isn’t just an instrument for backing up a singer. I worked hard and played for long hours every day to create a complex picking style that uses rhythmic syncopation and playing off the beat.”

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, many Afghan musicians in Peshawar returned to Kabul, but by this time, Sakhi was on his way to Fremont, California. He brought with him the sophisticated and original rubâb style that he had developed in Pakistan, but little else. Fremont, a city of some 200,000 that lies southeast of San Francisco, claims the largest concentration of Afghans in the United States. Afghans flocked to Fremont and nearby Hayward and Union City in the 1980s, joining an older community of émigrés from the Asian subcontinent. In Fremont, as in Peshawar, Sakhi established himself as a leader of the local musical community and he remains in high demand for performances, workshops and teaching.

Sakhi’s style has been shaped not only by the musical traditions to which Afghan music is geographically and historically linked, but by his lively interest in contemporary music from around the world. Sakhi composes, including for The Kronos Quartet and SARA, and has even collaborated with jazz musicians. After all he has experienced, Sakhi asks, “Why not?”

In addition to his work with SARA, Sakhi has his own international career, both as a soloist and collaborator, and with his group, The Sakhi Ensemble. He has appeared at such prestigious venues as NY’s Carnegie Hall, Paris’s Theatre De Ville, The World Sacred Music Festival in Fez, Morocco, and the Berlin Music Festival in Germany, as well as throughout the Middle East, and of course, he returns often to teach and perform in Kabul.

In December, 2011, Sakhi will collaborate with Hannibal Lokumbe, Liz Wright and the Philadelphia Symphony on The Music Liberation Project: Can You Hear God Crying. Sakhi has also been commissioned to compose and participate in a special concert series under the direction of Peters Sellers, and featuring Dawn Upshaw.

Homayoun Sakhi is featured on three volumes of Smithsonian Folkways Music of Central Asia CD series: Homayun Sakhi: The Art of Music of Afghanistan, Rainbow, Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov and Homayun Sakhi, and In the Footsteps of Babur: Musical Encounters from The Land of the Mughals.

Homayoun Sakhi & The Sakhi Ensemble

Homayoun Sakhi, rubâb

Zmarai Aref, tabla, dohlak

Khalil Ragheb, harmonium

Pervez Sakhi, rubâb, tula

And special guest vocalist

Ustad Farida Mahwash, vocals

Comprised of some of the most sought-after Afghan musicians living in the United States, The Sakhi Ensemble makes it concert debut at the Ojai Music Festival. The ensemble features Zmarai Aref (tabla, dohlak), Khalil Ragheb (harmonium), and Pervez Sakhi (rubâb, tula). In addition to artistic excellence, these musicians share a commitment to nurturing the next generation of musicians both here and in Afghanistan.

For more information contact us at [email protected]

Homayoun Sakhi is the most outstanding and innovative Afghan rubâb player of his generation, a brilliant virtuoso endowed with a charismatic musical presence and personality. The rubâb is the national instrument of Afghanistan. Homayon’s artistry demonstrates how an imaginative musician working within a traditional musical idiom can enrich and expand its expressive power while respecting the taste and sensibility passed down from master musicians of the past. Moreover, Sakhi is the Founder and Co-founder of today’s two foremost Afghan music ensembles, THE SAKHI ENSEMBLE and Sounds and Rhythms of Afghanistan (SARA). His soaring technique, melodic flair and unparalleled style have earned him global acclaim as the maestro on Afghan rubâb.

Sakhi was born in Kabul in 1976 into one of Afghanistan’s leading musical families. From the age of ten, he studied rubâb with his father, Ghulam Sakhi, in the traditional form of apprenticeship known as ustâd-shâgird (Persian: “master-apprentice”). Ghulam Sakhi was a disciple and, later, brother-in-law, of Ustâd Mohammad Omar (d. 1980), the much-revered heir to a musical lineage that began in the 1860s, when the ruler of Kabul, Amir Sher Ali Khan, brought classically trained musicians from India to perform at his court. The Amir gave these musicians residences in a section of the old city adjacent to the royal palace so that they could be summoned to court when needed, and this area, Kucheh Kharabat, became the musicians’ quarter of Kabul. Over the next hundred years, Indian musicians thrived there, and Kabul became a provincial center for the performance of North Indian classical music.

The royal patrons of this Afghan-Indian music also loved Persian culture and classical Persian poetry. To please their patrons, the Kharabat musicians created a distinctive form of vocal art that combined elements of Persian and Indian music. One of the principal Persian verse forms is the ghazal. Ghazals provided the texts for the new style of Afghan vocal music based on the melodic modes (raga) and metrical cycles (tala) of Indian music. The Kabuli style of ghazal singing later spread to other Afghan cities. The tabla, the pair of drums used in this new music to accompany the rubâb and express the music’s sophisticated rhythmic element, is indisputably Indian, but its creators seem to have drawn inspiration from older forms of Central and West Asian kettle and goblet drums.

The rubâb itself is a classical instrument with a folkloric past. It originated in Central Asia as long as 2000 years ago, and belongs to a family of double-chambered lutes that includes, among others, the Iranian târ, Tibetan danyen, and Pamir rubâb. After the rise of Islam, the rubâb was used to play a devotional style of traditional Afghan music called Khaniqa. The instrument then had five gut strings for melody and no sympathetic strings. Today, it has just three melody strings, made of nylon, and 14 or 15 sympathetic steel strings. The rubâb’s heavy body is constructed in three wooden parts: a carved hull, faceboard and headstalk. Goat skin is stretched over the body’s open face, taut like a banjo, and the melody strings pass through a bridge made from a ram’s horn. The classical rubâb technique developed under the influence of Indian and Persian music is almost like claw-hammer banjo picking, resulting in parallel melodies, incorporating both low and high drones interspersed with melody.

Homayoun Sakhi’s personal story illustrates the extraordinarily challenging conditions under which he and his fellow Afghan musicians have pursued their art. During Afghanistan’s long years of armed conflict, when music was controlled, censored, and finally, banned altogether, the classical rubâb style to which Sakhi had devoted his career not only survived but reached new creative heights. Sakhi’s musical studies were interrupted in 1992 when his entire family moved to the Pakistani city of Peshawar, a place of refuge for many Afghans from the political chaos and violence that enveloped their country in the years following the Soviet invasion of 1979. In Peshawar, Sakhi became a popular entertainer, playng a mixture of ragas and popular songs. Sakhi recalled, “I earned a good income from music. I played on television and on the radio. Peshawar has a lot of popular singers, and I played with many of them.”

The unofficial headquarters of Afghanistan’s émigré music community in Peshawar was Khalil House, a modern apartment building where some thirty or forty ensembles, including many Afgahn exiles, established offices. The building became the headquarters for musicians available to play wedding parties and other musical events. Some musicians ran their own music schools, and informal jam sessions where young musicians competed to show off their virtuosity and technical skills were common. Long hours and a spirit of camaraderie in Khalil House enabled the musicians from Kabul to maintain and further develop key musical skills.

Sakhi rented a room in Khalil House and opened a small music school. “The people of Peshawar,” Sakhi explained, “the way they play the rubâb is different. I introduced a Kabul style to them. For example, traditionally, rubâb players didn’t touch the instrument’s sympathetic strings, but I use them a lot, in addition to the melody strings. Before, players just picked down with the plectrum, but I picked both up and down. I thought these things up. I listened to violin music from different places, and to guitar and sitar music, and symphonic music. I listened to a lot of different things that I found on cassettes, and I wondered, why couldn’t I play with these kinds of techniques on the rubâb? I started to try them. I understood that the rubâb isn’t just an instrument for backing up a singer. I worked hard and played for long hours every day to create a complex picking style that uses rhythmic syncopation and playing off the beat.”

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, many Afghan musicians in Peshawar returned to Kabul, but by this time, Sakhi was on his way to Fremont, California. He brought with him the sophisticated and original rubâb style that he had developed in Pakistan, but little else. Fremont, a city of some 200,000 that lies southeast of San Francisco, claims the largest concentration of Afghans in the United States. Afghans flocked to Fremont and nearby Hayward and Union City in the 1980s, joining an older community of émigrés from the Asian subcontinent. In Fremont, as in Peshawar, Sakhi established himself as a leader of the local musical community and he remains in high demand for performances, workshops and teaching.

Sakhi’s style has been shaped not only by the musical traditions to which Afghan music is geographically and historically linked, but by his lively interest in contemporary music from around the world. Sakhi composes, including for The Kronos Quartet and SARA, and has even collaborated with jazz musicians. After all he has experienced, Sakhi asks, “Why not?”

In addition to his work with SARA, Sakhi has his own international career, both as a soloist and collaborator, and with his group, The Sakhi Ensemble. He has appeared at such prestigious venues as NY’s Carnegie Hall, Paris’s Theatre De Ville, The World Sacred Music Festival in Fez, Morocco, and the Berlin Music Festival in Germany, as well as throughout the Middle East, and of course, he returns often to teach and perform in Kabul.

In December, 2011, Sakhi will collaborate with Hannibal Lokumbe, Liz Wright and the Philadelphia Symphony on The Music Liberation Project: Can You Hear God Crying. Sakhi has also been commissioned to compose and participate in a special concert series under the direction of Peters Sellers, and featuring Dawn Upshaw.

Homayoun Sakhi is featured on three volumes of Smithsonian Folkways Music of Central Asia CD series: Homayun Sakhi: The Art of Music of Afghanistan, Rainbow, Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov and Homayun Sakhi, and In the Footsteps of Babur: Musical Encounters from The Land of the Mughals.

Homayoun Sakhi & The Sakhi Ensemble

Homayoun Sakhi, rubâb

Zmarai Aref, tabla, dohlak

Khalil Ragheb, harmonium

Pervez Sakhi, rubâb, tula

And special guest vocalist

Ustad Farida Mahwash, vocals

Comprised of some of the most sought-after Afghan musicians living in the United States, The Sakhi Ensemble makes it concert debut at the Ojai Music Festival. The ensemble features Zmarai Aref (tabla, dohlak), Khalil Ragheb (harmonium), and Pervez Sakhi (rubâb, tula). In addition to artistic excellence, these musicians share a commitment to nurturing the next generation of musicians both here and in Afghanistan.

For more information contact us at [email protected]  Homayoun Sakhi is the most outstanding and innovative Afghan rubâb player of his generation, a brilliant virtuoso endowed with a charismatic musical presence and personality. The rubâb is the national instrument of Afghanistan. Homayon’s artistry demonstrates how an imaginative musician working within a traditional musical idiom can enrich and expand its expressive power while respecting the taste and sensibility passed down from master musicians of the past. Moreover, Sakhi is the Founder and Co-founder of today’s two foremost Afghan music ensembles, THE SAKHI ENSEMBLE and Sounds and Rhythms of Afghanistan (SARA). His soaring technique, melodic flair and unparalleled style have earned him global acclaim as the maestro on Afghan rubâb.

Sakhi was born in Kabul in 1976 into one of Afghanistan’s leading musical families. From the age of ten, he studied rubâb with his father, Ghulam Sakhi, in the traditional form of apprenticeship known as ustâd-shâgird (Persian: “master-apprentice”). Ghulam Sakhi was a disciple and, later, brother-in-law, of Ustâd Mohammad Omar (d. 1980), the much-revered heir to a musical lineage that began in the 1860s, when the ruler of Kabul, Amir Sher Ali Khan, brought classically trained musicians from India to perform at his court. The Amir gave these musicians residences in a section of the old city adjacent to the royal palace so that they could be summoned to court when needed, and this area, Kucheh Kharabat, became the musicians’ quarter of Kabul. Over the next hundred years, Indian musicians thrived there, and Kabul became a provincial center for the performance of North Indian classical music.

The royal patrons of this Afghan-Indian music also loved Persian culture and classical Persian poetry. To please their patrons, the Kharabat musicians created a distinctive form of vocal art that combined elements of Persian and Indian music. One of the principal Persian verse forms is the ghazal. Ghazals provided the texts for the new style of Afghan vocal music based on the melodic modes (raga) and metrical cycles (tala) of Indian music. The Kabuli style of ghazal singing later spread to other Afghan cities. The tabla, the pair of drums used in this new music to accompany the rubâb and express the music’s sophisticated rhythmic element, is indisputably Indian, but its creators seem to have drawn inspiration from older forms of Central and West Asian kettle and goblet drums.

The rubâb itself is a classical instrument with a folkloric past. It originated in Central Asia as long as 2000 years ago, and belongs to a family of double-chambered lutes that includes, among others, the Iranian târ, Tibetan danyen, and Pamir rubâb. After the rise of Islam, the rubâb was used to play a devotional style of traditional Afghan music called Khaniqa. The instrument then had five gut strings for melody and no sympathetic strings. Today, it has just three melody strings, made of nylon, and 14 or 15 sympathetic steel strings. The rubâb’s heavy body is constructed in three wooden parts: a carved hull, faceboard and headstalk. Goat skin is stretched over the body’s open face, taut like a banjo, and the melody strings pass through a bridge made from a ram’s horn. The classical rubâb technique developed under the influence of Indian and Persian music is almost like claw-hammer banjo picking, resulting in parallel melodies, incorporating both low and high drones interspersed with melody.

Homayoun Sakhi’s personal story illustrates the extraordinarily challenging conditions under which he and his fellow Afghan musicians have pursued their art. During Afghanistan’s long years of armed conflict, when music was controlled, censored, and finally, banned altogether, the classical rubâb style to which Sakhi had devoted his career not only survived but reached new creative heights. Sakhi’s musical studies were interrupted in 1992 when his entire family moved to the Pakistani city of Peshawar, a place of refuge for many Afghans from the political chaos and violence that enveloped their country in the years following the Soviet invasion of 1979. In Peshawar, Sakhi became a popular entertainer, playng a mixture of ragas and popular songs. Sakhi recalled, “I earned a good income from music. I played on television and on the radio. Peshawar has a lot of popular singers, and I played with many of them.”

The unofficial headquarters of Afghanistan’s émigré music community in Peshawar was Khalil House, a modern apartment building where some thirty or forty ensembles, including many Afgahn exiles, established offices. The building became the headquarters for musicians available to play wedding parties and other musical events. Some musicians ran their own music schools, and informal jam sessions where young musicians competed to show off their virtuosity and technical skills were common. Long hours and a spirit of camaraderie in Khalil House enabled the musicians from Kabul to maintain and further develop key musical skills.

Sakhi rented a room in Khalil House and opened a small music school. “The people of Peshawar,” Sakhi explained, “the way they play the rubâb is different. I introduced a Kabul style to them. For example, traditionally, rubâb players didn’t touch the instrument’s sympathetic strings, but I use them a lot, in addition to the melody strings. Before, players just picked down with the plectrum, but I picked both up and down. I thought these things up. I listened to violin music from different places, and to guitar and sitar music, and symphonic music. I listened to a lot of different things that I found on cassettes, and I wondered, why couldn’t I play with these kinds of techniques on the rubâb? I started to try them. I understood that the rubâb isn’t just an instrument for backing up a singer. I worked hard and played for long hours every day to create a complex picking style that uses rhythmic syncopation and playing off the beat.”

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, many Afghan musicians in Peshawar returned to Kabul, but by this time, Sakhi was on his way to Fremont, California. He brought with him the sophisticated and original rubâb style that he had developed in Pakistan, but little else. Fremont, a city of some 200,000 that lies southeast of San Francisco, claims the largest concentration of Afghans in the United States. Afghans flocked to Fremont and nearby Hayward and Union City in the 1980s, joining an older community of émigrés from the Asian subcontinent. In Fremont, as in Peshawar, Sakhi established himself as a leader of the local musical community and he remains in high demand for performances, workshops and teaching.

Sakhi’s style has been shaped not only by the musical traditions to which Afghan music is geographically and historically linked, but by his lively interest in contemporary music from around the world. Sakhi composes, including for The Kronos Quartet and SARA, and has even collaborated with jazz musicians. After all he has experienced, Sakhi asks, “Why not?”

In addition to his work with SARA, Sakhi has his own international career, both as a soloist and collaborator, and with his group, The Sakhi Ensemble. He has appeared at such prestigious venues as NY’s Carnegie Hall, Paris’s Theatre De Ville, The World Sacred Music Festival in Fez, Morocco, and the Berlin Music Festival in Germany, as well as throughout the Middle East, and of course, he returns often to teach and perform in Kabul.

In December, 2011, Sakhi will collaborate with Hannibal Lokumbe, Liz Wright and the Philadelphia Symphony on The Music Liberation Project: Can You Hear God Crying. Sakhi has also been commissioned to compose and participate in a special concert series under the direction of Peters Sellers, and featuring Dawn Upshaw.

Homayoun Sakhi is featured on three volumes of Smithsonian Folkways Music of Central Asia CD series: Homayun Sakhi: The Art of Music of Afghanistan, Rainbow, Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov and Homayun Sakhi, and In the Footsteps of Babur: Musical Encounters from The Land of the Mughals.

Homayoun Sakhi & The Sakhi Ensemble

Homayoun Sakhi, rubâb

Zmarai Aref, tabla, dohlak

Khalil Ragheb, harmonium

Pervez Sakhi, rubâb, tula

And special guest vocalist

Ustad Farida Mahwash, vocals

Comprised of some of the most sought-after Afghan musicians living in the United States, The Sakhi Ensemble makes it concert debut at the Ojai Music Festival. The ensemble features Zmarai Aref (tabla, dohlak), Khalil Ragheb (harmonium), and Pervez Sakhi (rubâb, tula). In addition to artistic excellence, these musicians share a commitment to nurturing the next generation of musicians both here and in Afghanistan.

For more information contact us at [email protected]

Homayoun Sakhi is the most outstanding and innovative Afghan rubâb player of his generation, a brilliant virtuoso endowed with a charismatic musical presence and personality. The rubâb is the national instrument of Afghanistan. Homayon’s artistry demonstrates how an imaginative musician working within a traditional musical idiom can enrich and expand its expressive power while respecting the taste and sensibility passed down from master musicians of the past. Moreover, Sakhi is the Founder and Co-founder of today’s two foremost Afghan music ensembles, THE SAKHI ENSEMBLE and Sounds and Rhythms of Afghanistan (SARA). His soaring technique, melodic flair and unparalleled style have earned him global acclaim as the maestro on Afghan rubâb.

Sakhi was born in Kabul in 1976 into one of Afghanistan’s leading musical families. From the age of ten, he studied rubâb with his father, Ghulam Sakhi, in the traditional form of apprenticeship known as ustâd-shâgird (Persian: “master-apprentice”). Ghulam Sakhi was a disciple and, later, brother-in-law, of Ustâd Mohammad Omar (d. 1980), the much-revered heir to a musical lineage that began in the 1860s, when the ruler of Kabul, Amir Sher Ali Khan, brought classically trained musicians from India to perform at his court. The Amir gave these musicians residences in a section of the old city adjacent to the royal palace so that they could be summoned to court when needed, and this area, Kucheh Kharabat, became the musicians’ quarter of Kabul. Over the next hundred years, Indian musicians thrived there, and Kabul became a provincial center for the performance of North Indian classical music.

The royal patrons of this Afghan-Indian music also loved Persian culture and classical Persian poetry. To please their patrons, the Kharabat musicians created a distinctive form of vocal art that combined elements of Persian and Indian music. One of the principal Persian verse forms is the ghazal. Ghazals provided the texts for the new style of Afghan vocal music based on the melodic modes (raga) and metrical cycles (tala) of Indian music. The Kabuli style of ghazal singing later spread to other Afghan cities. The tabla, the pair of drums used in this new music to accompany the rubâb and express the music’s sophisticated rhythmic element, is indisputably Indian, but its creators seem to have drawn inspiration from older forms of Central and West Asian kettle and goblet drums.

The rubâb itself is a classical instrument with a folkloric past. It originated in Central Asia as long as 2000 years ago, and belongs to a family of double-chambered lutes that includes, among others, the Iranian târ, Tibetan danyen, and Pamir rubâb. After the rise of Islam, the rubâb was used to play a devotional style of traditional Afghan music called Khaniqa. The instrument then had five gut strings for melody and no sympathetic strings. Today, it has just three melody strings, made of nylon, and 14 or 15 sympathetic steel strings. The rubâb’s heavy body is constructed in three wooden parts: a carved hull, faceboard and headstalk. Goat skin is stretched over the body’s open face, taut like a banjo, and the melody strings pass through a bridge made from a ram’s horn. The classical rubâb technique developed under the influence of Indian and Persian music is almost like claw-hammer banjo picking, resulting in parallel melodies, incorporating both low and high drones interspersed with melody.

Homayoun Sakhi’s personal story illustrates the extraordinarily challenging conditions under which he and his fellow Afghan musicians have pursued their art. During Afghanistan’s long years of armed conflict, when music was controlled, censored, and finally, banned altogether, the classical rubâb style to which Sakhi had devoted his career not only survived but reached new creative heights. Sakhi’s musical studies were interrupted in 1992 when his entire family moved to the Pakistani city of Peshawar, a place of refuge for many Afghans from the political chaos and violence that enveloped their country in the years following the Soviet invasion of 1979. In Peshawar, Sakhi became a popular entertainer, playng a mixture of ragas and popular songs. Sakhi recalled, “I earned a good income from music. I played on television and on the radio. Peshawar has a lot of popular singers, and I played with many of them.”

The unofficial headquarters of Afghanistan’s émigré music community in Peshawar was Khalil House, a modern apartment building where some thirty or forty ensembles, including many Afgahn exiles, established offices. The building became the headquarters for musicians available to play wedding parties and other musical events. Some musicians ran their own music schools, and informal jam sessions where young musicians competed to show off their virtuosity and technical skills were common. Long hours and a spirit of camaraderie in Khalil House enabled the musicians from Kabul to maintain and further develop key musical skills.

Sakhi rented a room in Khalil House and opened a small music school. “The people of Peshawar,” Sakhi explained, “the way they play the rubâb is different. I introduced a Kabul style to them. For example, traditionally, rubâb players didn’t touch the instrument’s sympathetic strings, but I use them a lot, in addition to the melody strings. Before, players just picked down with the plectrum, but I picked both up and down. I thought these things up. I listened to violin music from different places, and to guitar and sitar music, and symphonic music. I listened to a lot of different things that I found on cassettes, and I wondered, why couldn’t I play with these kinds of techniques on the rubâb? I started to try them. I understood that the rubâb isn’t just an instrument for backing up a singer. I worked hard and played for long hours every day to create a complex picking style that uses rhythmic syncopation and playing off the beat.”

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, many Afghan musicians in Peshawar returned to Kabul, but by this time, Sakhi was on his way to Fremont, California. He brought with him the sophisticated and original rubâb style that he had developed in Pakistan, but little else. Fremont, a city of some 200,000 that lies southeast of San Francisco, claims the largest concentration of Afghans in the United States. Afghans flocked to Fremont and nearby Hayward and Union City in the 1980s, joining an older community of émigrés from the Asian subcontinent. In Fremont, as in Peshawar, Sakhi established himself as a leader of the local musical community and he remains in high demand for performances, workshops and teaching.

Sakhi’s style has been shaped not only by the musical traditions to which Afghan music is geographically and historically linked, but by his lively interest in contemporary music from around the world. Sakhi composes, including for The Kronos Quartet and SARA, and has even collaborated with jazz musicians. After all he has experienced, Sakhi asks, “Why not?”

In addition to his work with SARA, Sakhi has his own international career, both as a soloist and collaborator, and with his group, The Sakhi Ensemble. He has appeared at such prestigious venues as NY’s Carnegie Hall, Paris’s Theatre De Ville, The World Sacred Music Festival in Fez, Morocco, and the Berlin Music Festival in Germany, as well as throughout the Middle East, and of course, he returns often to teach and perform in Kabul.

In December, 2011, Sakhi will collaborate with Hannibal Lokumbe, Liz Wright and the Philadelphia Symphony on The Music Liberation Project: Can You Hear God Crying. Sakhi has also been commissioned to compose and participate in a special concert series under the direction of Peters Sellers, and featuring Dawn Upshaw.

Homayoun Sakhi is featured on three volumes of Smithsonian Folkways Music of Central Asia CD series: Homayun Sakhi: The Art of Music of Afghanistan, Rainbow, Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov and Homayun Sakhi, and In the Footsteps of Babur: Musical Encounters from The Land of the Mughals.

Homayoun Sakhi & The Sakhi Ensemble

Homayoun Sakhi, rubâb

Zmarai Aref, tabla, dohlak

Khalil Ragheb, harmonium

Pervez Sakhi, rubâb, tula

And special guest vocalist

Ustad Farida Mahwash, vocals

Comprised of some of the most sought-after Afghan musicians living in the United States, The Sakhi Ensemble makes it concert debut at the Ojai Music Festival. The ensemble features Zmarai Aref (tabla, dohlak), Khalil Ragheb (harmonium), and Pervez Sakhi (rubâb, tula). In addition to artistic excellence, these musicians share a commitment to nurturing the next generation of musicians both here and in Afghanistan.

For more information contact us at [email protected]